Disfigured and Gay |

|

|

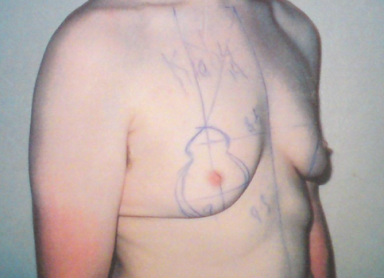

This story contains images of pre and post surgery.

I was fifteen when I first realised I was gay, at which time I was still suffering with ME and comfort-eating my way to becoming morbidly obese. I wasn’t in a position to have what others would call a ‘normal’ life – my world had collapsed in on itself, and the only people I saw on any regular basis were my immediate family. I didn’t have a social life or any friends and was too unwell to attend school, so although this discovery signified the beginning of an emotional struggle, it had very little impact on my reclusive little world – except to make me retreat even further into it. In many ways, my illness and ever-increasing waistline became the perfect disguise for my feelings – behind them I managed to keep my newly-acquired emotional struggle and self-loathing as secret as my binge-eating, with each contributing to and fuelling the other. |

Let’s skip ahead five years; by then I’d made a full recovery from ME, lost nearly 9 stone in weight, been disfigured from neck to knees by excessive folds of irreparably damaged skin (stretched beyond recognition by my former obesity) and was under the care of my Consultant Reconstructive Plastic Surgeon, who had begun the process of rebuilding my body with multiple-stage surgeries. Following one of my first operations I developed surgical complications that required emergency treatment to save my life.

"Back on the ward afterwards, it occurred to me that if I’d slipped away on the operating table, nobody would ever have known who I really was, and this realisation eventually became my motivation for coming out."

I had a lot to be grateful for; there was a long road ahead of me, but I was still alive, and it was time I stopped living my life like I was dead.

Little by little each operation pieced me back together, and while I began to look more ‘normal’, each round of surgery changed the way I regarded my own body; it wasn’t something to be touched, wanted or desired; it was a work-in-progress, a project, something that wasn’t ‘finished’ yet. I longed for the day when I would feel comfortable enough in my own skin to let someone touch me. I wanted to feel human again, to enjoy an intimate emotional and physical connection with a guy, but I found it hard enough touching my own body, and couldn’t bear the thought of someone else putting their hands on my damaged skin. I never felt attractive; at times I barely felt human, and I struggled to envisage a day when anyone would want to be with me.

To minimise my scarring, each operation required that I spend up to two months afterwards wearing surgical compression garments designed to contain swelling and ensure that the joins in my skin healed as flat as possible. Flesh coloured and unbearably tight, I wore them for twenty four hours a day, making the initial stages of recovery from each surgery feel like a prison sentence. Each one a nylon and lycra barrier that stood between me and the world, they made me feel even more isolated and alone; however, they were essential to my recovery, and I eventually learned to embrace them for the good I knew deep down that they were doing.

|

Over the two years it took for my skin to fully stabilise after each operation I carried out daily scar management routines. Twice a day I would spend an hour massaging and kneading the tough, contracting scars that streaked across my body with specialist treatment oils to restore suppleness and elasticity to my skin. |

As the treatments gradually wore away at my tough, fibrous scar tissue, I began to notice significant improvements to my overall levels of comfort. My skin became softer and more supple, and I began to experience a greater freedom of movement as the tension in the skin slowly decreased. Sensation began to return to the wounds and the surrounding tissue; as the treatments worked their magic my nerve endings started to regenerate and I began to experience peculiar trickling sensations where once I had been completely numb. I developed persistent itches that would last for months, but which left new nerve endings in their wake. Slowly but surely, bit by bit, I could feel my body starting to come back to life. With persistent scar management, by about 18 months after each surgery I could distinctly feel my fingers tracing across my skin, and hope began to kindle that maybe the scars weren’t, as I’d once thought, insurmountable obstacles standing between me and a “normal” future; perhaps I could get over this.

"As time passed I became slowly more at ease with the way I looked; I began to see my scars as badges of honour when I looked at my reflection in the mirror, and I wore them proudly."

I came to terms with the fact that my body would never look perfect; I no longer spent hours in the mirror grieving for my stolen childhood, for the body I might have had if I’d never been ill, for the person I might have been if I’d never gone through all this. I was stronger now. I no longer yearned for the physical perfection I’d once aspired to – no matter how hard I worked in the gym or how many hours I spent treating the skin, I would always have visible differences to other people – but I didn’t view that as a bad thing anymore. I had learned to accept myself, and that was almost enough

I started going swimming, and held my head up high in the locker room when I got changed; I walked down the road in summer with my top off and my war-wounds on display for the world to see. They would occasionally attract some negative attention; people would avoid my gaze and whisper amongst themselves, but I was determined not to let their ignorance stop me from living my life. People would stare, but for the most part I managed to ignore it; and what I couldn’t ignore, I did my best to put a positive spin on – maybe they secretly fancied me! Yet underneath my defiance, a nagging concern was gnawing away at me. I no longer feared hospitals, or needles, or pain; what I feared above all else was rejection. Not by my family – they had been incredibly supportive when I came out, and to this day I owe them so much for always being there to hold my hand when I’ve needed comfort, hold me up when I’ve needed support and push me forward when I’ve needed a kick up the arse.

I started going swimming, and held my head up high in the locker room when I got changed; I walked down the road in summer with my top off and my war-wounds on display for the world to see. They would occasionally attract some negative attention; people would avoid my gaze and whisper amongst themselves, but I was determined not to let their ignorance stop me from living my life. People would stare, but for the most part I managed to ignore it; and what I couldn’t ignore, I did my best to put a positive spin on – maybe they secretly fancied me! Yet underneath my defiance, a nagging concern was gnawing away at me. I no longer feared hospitals, or needles, or pain; what I feared above all else was rejection. Not by my family – they had been incredibly supportive when I came out, and to this day I owe them so much for always being there to hold my hand when I’ve needed comfort, hold me up when I’ve needed support and push me forward when I’ve needed a kick up the arse.

"I had survived everything life had thrown at me and come through it a stronger, wiser and more compassionate and caring person – but now I faced a very different challenge."

When I came out, I had been so insecure about the way I looked that I didn’t believe anyone would fancy me or want to touch my obesity-ravaged body. Throughout my illness, television and the internet had been my only tenuous links to the outside world, where gay men were (for the most part) portrayed as perfect physical specimens; they were always well groomed with flawless skin and tight bodies, and I was far from that – I was terrified that I may never be accepted in this apparently image-obsessed world looking the way I did. I tried to take pride in my appearance and make the best of what I had, but I’d learned to accept my imperfections; the question was, would anybody else? In a bid to continue moving forward and rebuilding my life I joined some online dating websites and tentatively started talking to people. I put a few pictures of my face online alongside some very basic information and started browsing through some other profiles. My heart sank.

“Fit blokes only”, “No chubby guys please”, “Only interested in slim / attractive lads”. Every guy’s profile seemed to express quite particular physical preferences when it came to describing their ‘type’.

While none of the profiles said “no disfigurements”, it seemed natural to conclude that being so explicit that “no lads over 25!!” need bother emailing also implied that scars would be met with similar rejection. When guys did email me, it wasn’t long into our conversations that I’d raise the subject; what was the point of lying? Usually my little revelation was a conversation stopper, and I nearly gave up on ever being accepted for who I was.

That was until the day I decided to turn it all around.

When I’d finally had enough of trying to dance around the subject during conversation I decided that, for the first time, I’d create a really honest profile, and wrote about everything I’d overcome. I was up-front with how much it had all affected me and open about how I felt it had made me a kinder, stronger and more empathetic person. I uploaded pictures of my scars for all to see, determined to convince myself that anyone who had a problem with them simply wasn’t worth my time. I still didn’t think anyone would find me attractive, but it was a powerful psychological turning point; whatever people thought of me, I wasn’t going to hide anymore.

That was until the day I decided to turn it all around.

When I’d finally had enough of trying to dance around the subject during conversation I decided that, for the first time, I’d create a really honest profile, and wrote about everything I’d overcome. I was up-front with how much it had all affected me and open about how I felt it had made me a kinder, stronger and more empathetic person. I uploaded pictures of my scars for all to see, determined to convince myself that anyone who had a problem with them simply wasn’t worth my time. I still didn’t think anyone would find me attractive, but it was a powerful psychological turning point; whatever people thought of me, I wasn’t going to hide anymore.

|

Then the messages started pouring in; “Congratulations on all your hard work – you look great!”, “Really interesting profile – you seem like a lovely guy!”, “I’m still losing weight and your profile has really encouraged me to keep going” – one by one people were messaging me to congratulate me, to compliment me, and to ask for help and advice; it was an amazing feeling, and each message I got put a massive grin on my face. I still told myself that people were just being nice, but to feel accepted for who I was and how I looked was an amazing feeling; it was these positive messages and words of support that encouraged me to keep fighting. On the odd occasion when someone would email me saying unkind things, I no longer took it to heart or let it eat away at me – instead, I just felt sorry for them. So what had changed? Why had my scars been such an elephant in the room before, where now they were the very thing that actually made people want to get in touch with me? The fear of putting myself out there and being rejected had been immense; I felt brow-beaten and battle weary and, frankly, this had clearly been apparent. I realised that I was the one responsible for presenting myself in a negative light, guilty of allowing myself to feel ashamed of my experiences and my appearance; when I chose instead to wear my heart on my sleeve and swap my shame for pride over what I’d accomplished, my whole attitude and outlook changed – and guys responded favourably to that. I was no longer a victim – I was a survivor. |

The more openly I talked about my disfigurement, the more acceptance I found; I began to understand that it wasn’t necessarily a barrier between me and other guys. My honesty was met with warmth and compassion, things I’d never expected to receive, let alone from guys my own age. I met some lovely, caring people, and despite feeling awkward and cripplingly self-conscious I eventually managed to let my guard down enough to have my first intimate encounters.

"Plucking up the courage to undress in front of someone took a lot of effort, but knowing that someone else had wanted to be with me, had seen past the scars and liked me for who I was, restored my sense of self-esteem and gave me renewed hope for a positive and happy future."

With these remarkable experiences fresh in my mind, my confidence has continued to grow day by day. The acceptance I’ve found has shown me how unfairly I once misjudged other gay men; while I’d expected them all to be squeamish, narcissistic and judgemental, not one of the guys I’d met had ever said anything nasty or critical about my body or rejected me because of my scarring. Being disfigured hadn’t mattered anymore because I was gay than it would have if I’d been straight; in fact, it mattered a lot less than I’d previously allowed myself to believe. Of course there are days when I don’t feel like this, and when my appearance gets me down more than others, but during those times I’ve learnt to hang onto these positive memories.

My advice to other young gay people living with a disfigurement is to never, ever give up hope; I’m living proof that it’s possible to be scarred, gay and happy. It’s natural (and perfectly okay) for these experiences to make you feel isolated and alone; dealing with so much stigma all at once can feel like stepping off one emotional rollercoaster and straight onto another, but it IS possible to come through all that and regain your balance. Granted, you might initially feel a little less steady on your feet than others, but when the room stops spinning you’ll have your feet planted firmer on the ground than ever before. Before I accepted and embraced who I was, I was carrying the weight of the world on my shoulders; now that I’m comfortable with who I am inside and out, I feel as though I’m standing on top of it.

My advice to other young gay people living with a disfigurement is to never, ever give up hope; I’m living proof that it’s possible to be scarred, gay and happy. It’s natural (and perfectly okay) for these experiences to make you feel isolated and alone; dealing with so much stigma all at once can feel like stepping off one emotional rollercoaster and straight onto another, but it IS possible to come through all that and regain your balance. Granted, you might initially feel a little less steady on your feet than others, but when the room stops spinning you’ll have your feet planted firmer on the ground than ever before. Before I accepted and embraced who I was, I was carrying the weight of the world on my shoulders; now that I’m comfortable with who I am inside and out, I feel as though I’m standing on top of it.

"People won’t reject you as long as you have learnt to accept and love, yourself. Don’t be scared to open your heart to people and be honest about your feelings – their reactions might just surprise you."

Kristian runs the website M.E. Myself and I which provides information on a variety of topics such as ME (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) / CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), Obesity, Weight Loss and reconstructive surgery. It also explores Kristian's experiences further, showing that no amount of adversity can destroy you unless you let it.

@KristianNorman

@MEandMe_Org

www.MEandMe.org

HTML Comment Box is loading comments...